What (Exactly) is an App?

By Warren Buckleitner, February 25, 2015

It took a rogue pediatrician in Utah to inspire this article. You see, for Dr. Nygaard, an app is like a toxin. But others might see this same app as a tutor, a link to a Grandparent or a programming experience. This article looks at screen content from a social-cultural point of view, which is important to do if you’re in the business of rating, making or using screen-based content with children.

What (exactly) is an app? It’s complicated.

“The studies are pretty impressive that show in every exposure a child has to screens, there is a risk of them developing ADD,” Marty Nygaard, Pediatrician, Red Rock Pediatrics in St. George, Utah, in the St. George Daily Spectrum, Sunday Feb. 1, 2015.

As you can see by Dr. Nygaard’s comment, confusion and fear of things like ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) tend to be the default condition when it comes to discussions of screens, including those running children's apps (he doesn't make any distinction).

Like the inkblots used in a Rorschach test, what is a “screen” or an “app” depends on what you expect to see. To this particular pediatrician, a screen is something bad that might cause irreversible damage. But others might see something very different.

An appropriate metaphor is the classic blind men meet an elephant fable. The elephant, in this case, is the app. In order to make headway in discussions around children’s interactive media, we must rethink how we define the modern children’s app.

FIRST, SOME HISTORY. Back in 1980, when both this field and I were young, researchers understood that a microcomputer was a chameleon. For Dustin Heuston, who worked on tutorial systems like WICAT it was CAI (computer aided instruction) and for others, like Seymour Papert, it was something for children to program. One solution was to define three roles: tool, tutor and tutee (see Taylor 1980, for an early mention of these categories).

Microcomputers have since morphed into connected phones or tablets with multi-touch screens. Putting all the apps into three buckets isn’t so easy anymore. One way to deal with the ambiguity is to admit defeat. There is no way to simply define or categorize an app. Apps consists of pictures, sounds, ideas and video that swim in an interactive soup created by a designer with distinct ideas about how much control a child should have.

The solution I propose is to take an anthropological point of view of "the app." Start the exercise by first viewing each app as a human artifact, sort of like a clay pot, a hammer or the foundation of a building, and then exploring the culture behind the app. What was the intention of the designer or team of designers? How much do they know about teaching and learning? How do they define things like “story,” “play,” “teaching,” and “learning?” What words (or jargon) do they use to define these ideas? What conferences do they attend, and what books or blogs do they read?

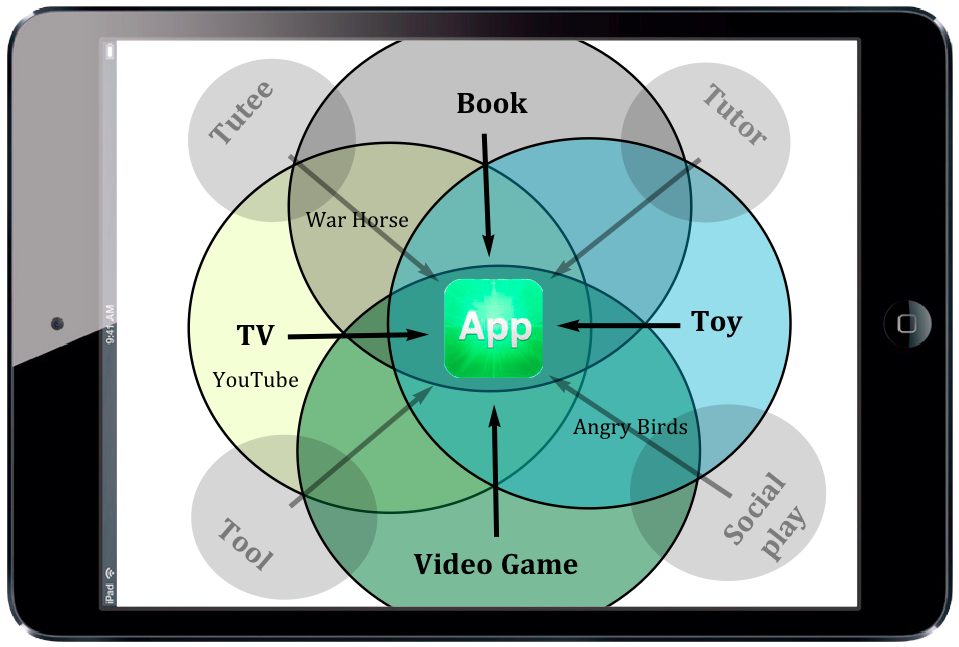

When you take this approach, you can create a Venn diagram with overlapping circles that represent each cultural cluster.

This, or a cross tagging mechanism such as what we use for CTREX, can make it possible for an app to fit inside multiple categories. By viewing the app store through the Venn diagram lens, you can account for all the messy and interesting overlaps between the categories and their associated cultures. It helps you begin to compare similar products, and it helps us understand attributes associated with higher or lower ratings.

Here’s a look at some of the most common circles that influence children’s app design. What follows contains one person’s point of view, along with some stereotyping, so let me apologize in advance.

EDUCATORS gather each year at conferences like MACUL, NECC and FETC to discuss apps and app design, especially to support the Common Core so that “no child will be left behind” in the “race to the top.” Some concern themselves with mastery of objectives and individualized learning. Educators can be very vocal about the use and misuse of digital pedagogy. Some use technology for open-ended child empowerment (see Code.org); others see an iPad as the ultimate Skinner box, where they can train a child to understand anything. To any seasoned teacher, “gamification” is old hat. They’ve been doing it for years by turning spelling practice into a spelling bee, for example. The ideal app example is something like Slice Fractions, which was made by a design team with a background in both video game design and Math Pedagogy.

THE TOY INDUSTRY will be very visible at next week’s Toy Fair. They will turn smart phones and tablets into remote controls or augmented reality tools to supplement (and market) toys. Apps are great extensions of IP (intellectional property) that can help you reach new markets. Hasbro’s Furby Boom uses audio codes to interact with a nearby tablet or smart phone, so that Furby can have babies. Direct income from apps is merely pocket change. But it can give you a new reason to buy another Furby. Toy giant LEGO has spawned dozens of well-designed video games and apps as well as a movie. The games, created for LEGO by TT Games are stellar examples of how a toy brand can be turned into a video game with strong educational objectives (in this case, collaborative problem solving). Toca Boca brings a fresh new voice to the app/toy relationship, because it thinks of it’s apps as toys, with no wrong answers.

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK INDUSTRY likes to migrate to places like the Bologna Children’s Book Fair where quality illustration and storytelling is celebrated (disclosure, CTR is a business partner with the fair). An app may be something with a blend of good narrative that could be fiction or non-fiction. When this work comes to a touch screen, it can assume many names: “ebooks,” “living books,” “digital story books,” or even “app books.” Children’s book developers respect the original paper books. They include Oceanhouse Media, who specializes in turning printed books into apps. Children’s book publishers like Kate Wilson of Nosy Crow have demonstrated that a solid story like Jack and the Beanstalk can work well on a touch screen. War Horse, the Touch Press app that won the BolognaRagazzi Digital Prize last year contains the full text of the original book, as well as a movie of the author reading the story and real-time links to Google Earth. War Horse is an app with multiple personalities, each with a different dot on the Venn Diagram.

THE VIDEO GAME INDUSTRY meetsup with other "gamers" at conferences like GDG and E3 to gossip about Zelda and discuss game mechanics. A video is called a “cut scene” and illustrations are called “graphics.” The video game culture is much newer than the others, but it’s extremely influential in part because it’s all about the interactivity. Video Game controllers are always extremely responsive and foster feelings of empowerment. Video game designers think a lot more about leveling and inter-personal problem solving that have a lot to say about IAP (in app purchases). Noteworthy contributions include Farmville, Angry Birds and Mojang’s Minecraft; all have deep roots in the gaming culture. Video game publishers are generally angry these days, because $2 apps are eating into their ability to sell $50 games that run on hardware they control. But when it comes to apps, they’ll help you figure out how to turn a crossword puzzle into Words With Friends, serving up ads on a “freemium” version. Or they can take a tried-and-true game mechanic and turn it into something like Angry Birds.

TV (and film) culture members read KidScreen and go to Cinekid in Amsterdam, if they’re lucky. When they get involved with learning, they search for a cute star like Elmo, Blue or Curious George; and they can pull out a Fred Rogers quote at the drop of hat. They know how to make things look great on a screen with camera angles and professional voice talent. The episodes they produce have a start, middle and an end, and they stick to the script. If the child leaves the room, it doesn’t matter... their production will continue to enlighten an empty room. It is easy to find examples of “dust” when it comes to porting TV characters into interactive apps. In the post-YouTube years, however, linear media producers have learned to convert a tablet into a touch screen remote, to serve up bite-sized episodes on mobile screens. Learn more about the science behind Dreamworks TV, the Nick Jr. app, or Vinekids.

There are more loops that could go into the Venn diagram. Each can help answer the question, “what is an app?” We have to settle with the idea that there is no clean answer, and the app store categories like “game” and “education” will never be accurate. But you can get closer to understanding the topic if you look at a lot of different types of apps, and think about the culture that has informed their design process.

———————

Thanks to David Hilgen, David Kleeman, Robin Raskin, Scott Traylor and Sarah Buckleitner for their feedback on this article.